DID Birkenhead and Wirral really inspire the greatest science fiction novelist of all time to write some of his world famous books?

That’s the belief of John Lamb, 61, who claims he has discovered irrefutable links between Jules Verne and Birkenhead, most famous for its Cammell Laird shipyard, the world’s first public park and Tranmere Rovers. Promoting this connection could be transformational for Birkenhead’s fortunes, he says.

Lamb, a former geography teacher born in Birkenhead and who now lives in Allerton, has worked for years to uncover the potential relationship between Jules Verne ‘father of science fiction’ and Birkenhead.

Lamb, a former geography teacher born in Birkenhead and who now lives in Allerton, has worked for years to uncover the potential relationship between Jules Verne ‘father of science fiction’ and Birkenhead.

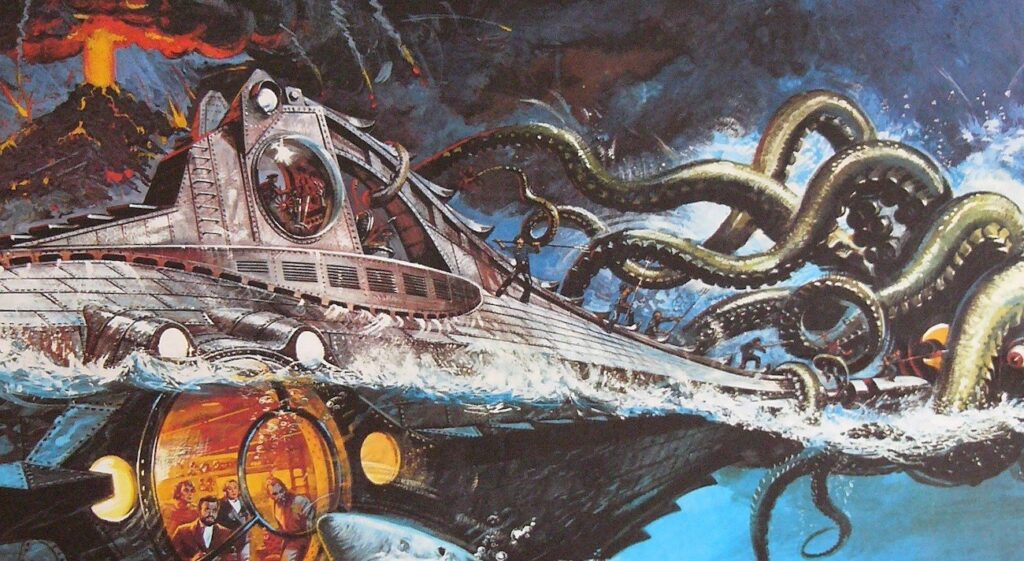

The fame of great shipyards is usually burnished by the names of their most famous vessels. Bizarrely for Cammell Laird the contender could be entirely fictional: Jules Verne’s submarine Nautilus, as featured in his novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and seen above (Jetsettimes.com/Paris/Steampunk).

John has painstakingly researched Verne’s works and also the history of the Mersey shipyard, in particular the construction of its infamous warship CSS Alabama, also ‘builder’ of five more of Verne’s fictional ships.

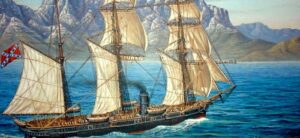

Alabama, an American Civil War Confederacy raider, caused devastation to the Northern States’ shipping, resulting in Britain being the first country to be sued in the international courts for violating its official neutrality.

What’s more John claims there are strong links between Alabama and Nautilus, although the former was a wooden coal-fired steam and sail powered surface ship (right) while Nautilus was a highly advanced submarine.

former was a wooden coal-fired steam and sail powered surface ship (right) while Nautilus was a highly advanced submarine.

“Laird’s was a pioneer in building pre-fabricated ships, like the steam launch Ma Roberts for missionary Dr David Livingston’s Zambesi exploration. Both Alabama and Nautilus were largely prefabricated and completed on desert islands.

“Designed to roam oceans on a global scale attacking other ships, both vessels also met their demise off Cherbourg (Alabama sinking on right). It’s Verne’s genius that he can base a futuristic submarine on a wooden warship.”

“Designed to roam oceans on a global scale attacking other ships, both vessels also met their demise off Cherbourg (Alabama sinking on right). It’s Verne’s genius that he can base a futuristic submarine on a wooden warship.”

The 800 page diary of Capt Raphael Semmes, master of Alabama, (right below) reveals he was an academic from Mobile, Alabama, and Nautilus’ (fictional) commander, Capt Nemo’s motto was ‘Mobilis in Mobile’. John believes they are alter egos and Nemo is a metaphor for the US Civil War’s turmoil. He says: “Nemo was a tormented soul who hates war, slavery and imperialism. Both described experiences like sailing through coral mausoleums, white water and sheltering in an extinct volcanic island.

from Mobile, Alabama, and Nautilus’ (fictional) commander, Capt Nemo’s motto was ‘Mobilis in Mobile’. John believes they are alter egos and Nemo is a metaphor for the US Civil War’s turmoil. He says: “Nemo was a tormented soul who hates war, slavery and imperialism. Both described experiences like sailing through coral mausoleums, white water and sheltering in an extinct volcanic island.

“The deadly exploits of CSS Alabama were like nothing seen in the world before and shipping insurance shot up around the world. Verne’s attitude was like baking a Jamie Oliver cake – he just chucked everything to do with Alabama into his novels. Semmes believed India should remain under British rule, so Verne makes Nemo an Indian prince who fought against Britain. Verne had a mischievous modern sense of humour which shines though. He was also a bit of a loony!

No better example of Verne’s novelising events was that of the Bostonian transport magnate George Francis Train, who built the UK’s first tramway in Birkenhead and went around the world in 80 days. Train wasn’t happy about the outcome and his alleged portrayal, raging: “Verne made fiction of my fact and stole my thunder. I’m Phileas Fogg!”

No better example of Verne’s novelising events was that of the Bostonian transport magnate George Francis Train, who built the UK’s first tramway in Birkenhead and went around the world in 80 days. Train wasn’t happy about the outcome and his alleged portrayal, raging: “Verne made fiction of my fact and stole my thunder. I’m Phileas Fogg!”

Verne and Birkenhead have modern image problems, with the latter’s glory days long gone. Verne is seen as a children’s author and false prophet. Yet Verne’s first visit abroad from France was to Liverpool, second city of the British Empire and thence across the Mersey to Birkenhead.

Back then members of the Royal Mersey Yacht Club (right below) were like a roll call of world famous men including the Vanderbilts and Roosevelts. Former First Lady of the US Eleanor Roosevelt’s great uncle James Dunwoody Bulloch was a Confederate spy in Liverpool who ordered CSS Alabama. Birkenhead resident FS Hull was the Confederate’s solicitor who got round international laws on its behalf (for a while)

including the Vanderbilts and Roosevelts. Former First Lady of the US Eleanor Roosevelt’s great uncle James Dunwoody Bulloch was a Confederate spy in Liverpool who ordered CSS Alabama. Birkenhead resident FS Hull was the Confederate’s solicitor who got round international laws on its behalf (for a while)

The great international Wirral-born engineer Thomas Brassey, based in Birkenhead, was also praised by Verne. Brassey was friends with the other great British engineers Brunel and the Stephensons. It seems everyone knew everyone else.

“Over a period of 20 years Birkenhead was a microcosm of advancing world technological and engineering activity. It was part of the American ‘Gilded Age’. Brassey and the US financier Cyrus Field repurposed Brunel’s huge ill-fated steam ship Great Eastern (left) to lay the first transatlantic cable.”

“Over a period of 20 years Birkenhead was a microcosm of advancing world technological and engineering activity. It was part of the American ‘Gilded Age’. Brassey and the US financier Cyrus Field repurposed Brunel’s huge ill-fated steam ship Great Eastern (left) to lay the first transatlantic cable.”

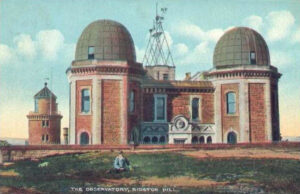

Bidston Hill’s Lighthouse and Observatory (below) were the inspiration for the volcanoes in Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), The Mysterious Island (1873) and the observatory in The Floating Island (1895), John claims.

inspiration for the volcanoes in Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), The Mysterious Island (1873) and the observatory in The Floating Island (1895), John claims.

“Verne was a theatre set designer and this shows. In Journey the tunnel from the volcano is based on Brassey’s Great Culvert Sewer in Birkenhead and the underground sea is the Mersey,” he speculates. The story’s 12ft high giant could be based on the Childe of Hale (who was 9′ 3″) resident of the village across the Mersey.

“A cross referenced approach showing how Verne uses Bidston Lighthouse across three entirely different novels is the best way to get concepts across. Give it to a judge who’s an expert in plagiarism!”

“A cross referenced approach showing how Verne uses Bidston Lighthouse across three entirely different novels is the best way to get concepts across. Give it to a judge who’s an expert in plagiarism!”

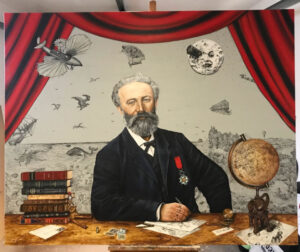

“There are 60 Wirral locations whose distances and direction to one another all match those in The Mysterious Island. The Wirral peninsula becomes the island – again that’s genius of the man (painting above left by Catt Landa).

“Jules Verne could do for Birkenhead what the Shakespeare North Playhouse is doing for Prescot. Verne is the world’s second most translated author ahead of Shakespeare and was quoted on the first Moon landing by Neil Armstrong. What better hero could Birkenhead want?”