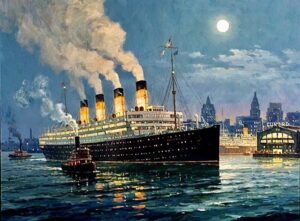

SEVENTY-five years ago, this week one of Liverpool’s – if not the world’s – greatest ocean liners sailed into Gareloch, Scotland, under her own steam to be broken up at Faslane.

SEVENTY-five years ago, this week one of Liverpool’s – if not the world’s – greatest ocean liners sailed into Gareloch, Scotland, under her own steam to be broken up at Faslane.

After an incredible 36-year career beginning in 1914, Cunard Line’s RMS Aquitania, the last of the Edwardian four funnelled superliners, finally rang ‘finished with engines’ on her bridge telegraph for the last time on 21 February, 1950.

Aquitania, or ‘The Aqui’ (everything in Liverpool gets a nickname) steamed from the ragtime era almost into the rock ‘n’ roll age, sailing heroically through two world wars, and in commercial service during the peace before, between and after both conflicts, through the toughest oceans.

Aquitania, or ‘The Aqui’ (everything in Liverpool gets a nickname) steamed from the ragtime era almost into the rock ‘n’ roll age, sailing heroically through two world wars, and in commercial service during the peace before, between and after both conflicts, through the toughest oceans.

Not only was Aquitania one of the biggest and most popular premier liners on the UK- New York ‘Atlantic ferry’ when there was no alternative to sea travel but also served her country as a hospital and troopship during wartime. Always a lucky ship, she avoided being sunk or bombed, despite being high on Hitler’s big ship hit list and some near misses.

travel but also served her country as a hospital and troopship during wartime. Always a lucky ship, she avoided being sunk or bombed, despite being high on Hitler’s big ship hit list and some near misses.

She survived the 1929 Wall Street Crash and the Depression which decimated passenger numbers, with redeployment on short Mediterranean cruises. Her supremely elegant country house-style First-Class interiors earned her the soubriquet ‘The Ship Beautiful’.

These interiors by the top interior designer Arthur Davis kept her clientele loyal in spite of the new generation of flashy French and German art deco superliners. Unexpectedly, her basic Third-Class bare steel cabins inspired the modernist architect Le Corbusier’s diktat of ‘Function is beauty’ in his seminal modernist Villa Savoye, in Poissy, France.

These interiors by the top interior designer Arthur Davis kept her clientele loyal in spite of the new generation of flashy French and German art deco superliners. Unexpectedly, her basic Third-Class bare steel cabins inspired the modernist architect Le Corbusier’s diktat of ‘Function is beauty’ in his seminal modernist Villa Savoye, in Poissy, France.

Once Cunard Line’s new record-breaking RMS Queen Mary was in service, Aquitania’s engines were retuned twice so she could maintain a schedule alongside the new speed queen. Indeed, Aquitania got faster as she got older, a great tribute to her builders, Clydebank’s John Brown & Co. Finally her top speed was an impressive 25 knots (29mph).

were retuned twice so she could maintain a schedule alongside the new speed queen. Indeed, Aquitania got faster as she got older, a great tribute to her builders, Clydebank’s John Brown & Co. Finally her top speed was an impressive 25 knots (29mph).

This was surprising as she wasn’t built for speed but to rival the luxury of White Star Line’s Olympic class trio (of which Titanic was the second).

After the Second World War, she repatriated US and Canadian servicemen and then operated a UK emigrant service to Halifax, Nova Scotia (below left), carrying thousands of Canadian war brides and children.

I was lucky enough to interview one of the liner’s last pursers, Charlie Sutherland, from Crosby, who had some fond memories. He recalled: “The Aqui was due to be withdrawn when the new Queen Elizabeth came into service in 1940.

I was lucky enough to interview one of the liner’s last pursers, Charlie Sutherland, from Crosby, who had some fond memories. He recalled: “The Aqui was due to be withdrawn when the new Queen Elizabeth came into service in 1940.

“Instead, the war extended her career by another 10 years, often sailing in convoy with Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary. After the war, in repatriation and emigrant service, if anything broke it wasn’t fixed to save money.

“We had all these young women aboard and there was a lot of paperwork to sort out before their arrival in Halifax. This included contacting the church parishes where the women would live, so the chief purser got the women to help. Unfortunately, the weather was often rough and many of them were sick into the typewriters!

their arrival in Halifax. This included contacting the church parishes where the women would live, so the chief purser got the women to help. Unfortunately, the weather was often rough and many of them were sick into the typewriters!

“Then he had the brainwave of simply dividing them by surname into likely religious denominations. So English surnames were listed as Anglicans, Irish names as Catholics, Welsh as Baptist, and Scots as Presbyterians.

“Of course, it was a mess and once the women were in their parishes, Catholic priests were going round to call on red-hot Orange Lodgers and so on. There was a hell of a row, but we never got found out!”

After failing her Board of Trade operating certificate in December 1949 she was withdrawn. Scrapping was finally completed in November 1951. Overall, she steamed three million miles round the world (with 500,000 miles in wartime), made 450 transatlantic round voyages, carried 1.2 million passengers and 300,000 service men. She was the 20th century’s longest serving express liner, and the longest serving with one company.

After failing her Board of Trade operating certificate in December 1949 she was withdrawn. Scrapping was finally completed in November 1951. Overall, she steamed three million miles round the world (with 500,000 miles in wartime), made 450 transatlantic round voyages, carried 1.2 million passengers and 300,000 service men. She was the 20th century’s longest serving express liner, and the longest serving with one company.

That’s an astonishing return on investment!